Laughter

Electrical stimulation of specific sites of the brain can cause laughter.

These sites include the subthalamic nucleus, anterior cingulate cortex, superior frontal gyrus, frontal operculum, and basal temporal cortex.

While this is less dangerous than other reactions if abused, it could still do such things like an individual being discredited as a dubious person who laughs out of nowhere in an inappropriate situation.

Table of ContentsAll_Pages

Circuitry

Humans

Since animals were only recently discovered to laugh, the laughter circuitry has been explored within the limited framework of human research.

The experiments on electrical stimulation of the human brain have identified several regions that induced laughter.

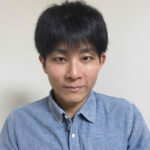

Lateral cortical regions include the superior frontal gyrus (supplementary motor area and pre-supplementary motor area) and the basal temporal cortex (inferior temporal gyrus, fusiform gyrus, and parahippocampal gyrus).

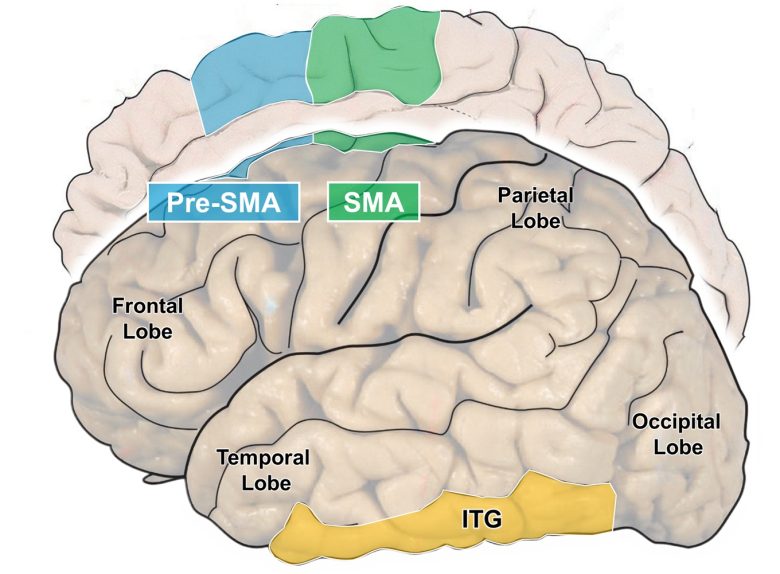

Medial cortical regions include the anterior cingulate cortex, insular cortex, and frontal operculum.

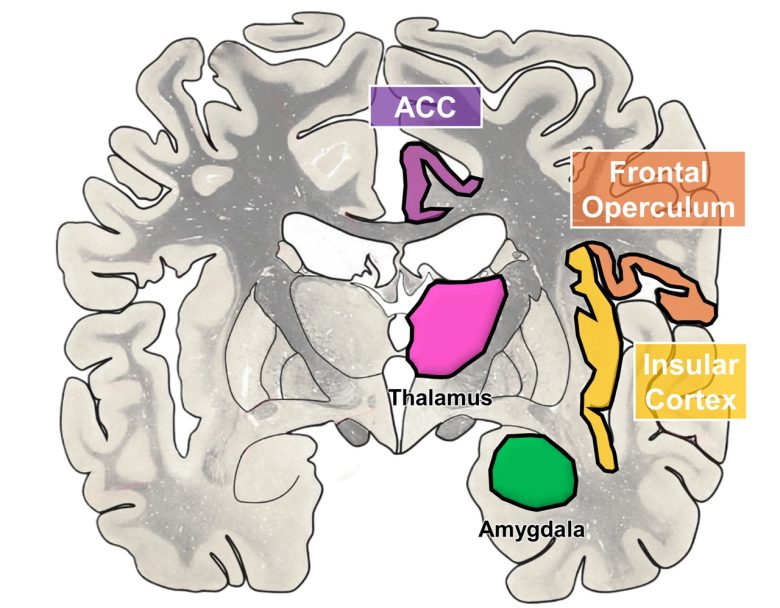

Deep brain regions include the subthalamic nucleus and nucleus accumbens.

The lateral cortical regions where electrical stimulation induces laughter (the superior frontal gyrus)

(The brain image from Vanderah 2018)

SMA = supplementary motor area; ITG = inferior temporal gyrus.

The lateral cortical regions where electrical stimulation induces laughter (the basal temporal cortex)

(The brain image from Vanderah 2018)

PHG = parahippocampal gyrus; FG = fusiform gyrus; and ITG = inferior temporal gyrus.

The medial cortical regions where electrical stimulation induces laughter

(The brain image from Vanderah 2018)

ACC = anterior cingulate cortex.

The deep brain regions where electrical stimulation induces laughter

(The brain image from Vanderah 2018)

NAc = nucleus accumbens; STN = subthalamic nucleus; CC = cingulate cortex; ACC = anterior cingulate cortex.

Animals

Dr. Jaak Panksepp, a pioneer in affective neuroscience, discovered that when rats are tickled, they emit ultrasonic chirps at 50 kHz, which humans cannot hear. (Panksepp and Burgdorf 2003)

The doctor considered this to be the equivalent of human laughter.

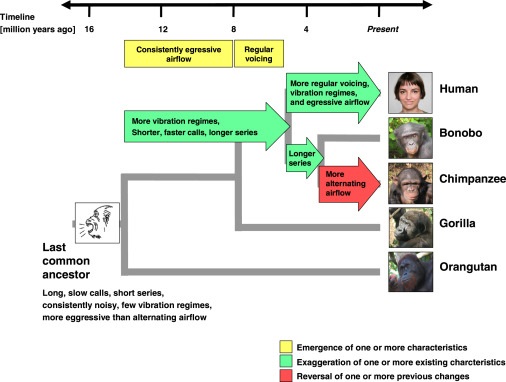

A study from the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Germany, has found that the laughter elicited by tickling is homologous in human infants and great ape infants, meaning it was inherited from the common ancestor. (Davila Ross et al. 2009)

Therefore, at least as far as apes are concerned, attributing the emotion of laughter to them is not anthropomorphism; they are truly laughing, just like humans.

Recently, UCLA researchers have shown that 65 animal species produce laughter-like vocalizations while playing. Winkler and Bryant 2021)

This included mammals such as humans, apes, many primates, rats, dogs, cats, bears, killer whales, dolphins, elephants, foxes, cows, and kangaroos, as well as three bird species.

Humans

These animals may be useful as model organisms for elucidating the neural circuits of laughter in the future.

It has been shown that laughter can be induced by electrical stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus, anterior cingulate cortex, superior frontal gyrus, frontal operculum, insular cortex, basal temporal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and hypothalamic hamartomas.

Subthalamic Nucleus

Researchers at the University of Grenoble in France reported two cases in which laughter was induced by electrical stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus. (Krack et al. 2001)

The first patient was a 47-year-old male with Parkinson's disease, and continuous electrical stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus had been administered to him as treatment.

On one occasion, the pulse width of the electrical stimulation was increased from 60 to 90 ms in order to further improve his parkinsonism.

The following day, the patient returned complaining of ongoing bursts of laughter.

He and his wife initially found the laughter amusing. His mood was elevated.

The laughter eventually became annoying and uncomfortable, as it was inappropriate, almost uncontrollable and exhausting, although the patient still felt amused when laughing and his mood stayed elevated even in between bursts of laughter.

After the pulse width was decreased to 60 ms again, the bursts of laughter immediately disappeared.

Two months later, the pulse width was increased again from 60 to 90 ms experimentally, with the informed consent of the patient, in order to study this side effect in more detail.

One minute after the pulse width was increased, the patient started to tap his thigh repeatedly with his right hand. When asked why he did this, he answered that this felt right.

After 5 minutes, he reported feeling light-headed. Shortly thereafter, he had a first burst of laughter accompanied by merriment. He exhibited a smiling face with a puzzled look, loud laughing, repeatedly tapping his thighs with both hands and repeatedly hitting the floor with his feet.

His movements were so ample that he was almost thrown off his chair.

His mimicry and gestures led one to think that he amused himself, and indeed the patient himself found the whole situation funny. He was constantly looking around, screening his environment with an expression of amused interest.

He had very vivid associations and made puns. The laughter was highly infectious and several neurologists and neurosurgeons who were present in the room also fell into hilarity.

For example, when looking at the nose of Professor Benabid, the patient thought of the nose of Cyrano de Bergerac and started another burst of laughing pointing with his finger at Professor Benabid’s face.

When Dr. Krack could not restrain himself anymore and fell into a burst of laughter, the patient shouted ”il craque” (he has a burst) and this pun led to a generalized burst of laughter of all the people present including the patient.

That he could hardly control his laughter became unpleasant with time and he asked whether we could stop making him laugh.

After stimulation arrest, parkinsonism reappeared within less than a minute and the laughter gradually diminished.

After stimulation resumption, parkinsonism disappeared and the laughter rapidly returned.

The second patient was a 54-year-old male with Parkinson's disease, and likewise continuous electrical stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus had been administered to him as treatment.

In an attempt to further improve his parkinsonism, stimulation amplitude was gradually increased from 3.2 V to 5.0 V.

Shortly thereafter, the patient developed intermittent bursts of laughter which continued for several minutes until the voltage was reduced to 3.2 V.

The following week, with the informed consent of the patient, the stimulation amplitude was gradually increased to 5.0 V over a 10-minute period when he started to smile spontaneously because he thought that Dr. Kumar’s bent spectacles made his head look odd.

One minute after the amplitude was increased to 5.5 V, the patient started to laugh in response to the question, “Do you feel anxious or nervous?”

When asked why he was laughing, he joked, “One could say I am laughing because I am over-stimulated.”

Intermittent laughter continued thereafter and he developed rhythmical left leg dyskinesias.

Although he had experienced dyskinesias in the past, he found this new type of dyskinesia to be quite amusing and this provoked a new round of laughter.

The excessive laughter resulted in him saying, “I don’t think that my brain is getting enough oxygen.”

After another minute of intermittent laughter he remarked, “I feel a need to rebel and then I start to laugh. That’s not very rebellious is it.”

In the following minutes, he repeatedly had bursts of laughter accompanied by merriment.

The patient finally requested that stimulation be discontinued. Dyskinesias and intermittent laughter persisted for 5 minutes before the left arm tremor returned and mirth subsided.

Anterior Cingulate Cortex

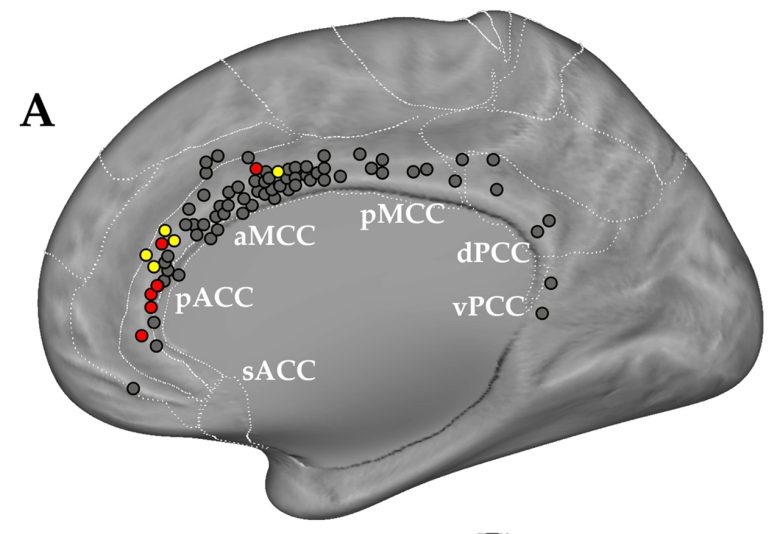

An experiment was conducted at the University of Parma in Italy to investigate the role of the anterior cingulate cortex in laughter. (Caruana et al. 2015)

The subjects were 57 epilepsy patients, and electrical stimulation of the anterior cingulate cortex induced laughter in 10 of them.

The sites that induced laughter were concentrated in the pregenual part of the anterior cingulate cortex (pACC).

In five patients, the stimulation elicited a burst of laughter with mirth. In these patients the effect of the stimulation was not restricted to the production of a facial expression, but also elicited a clear feeling of mirth.

More specifically, patients arrested the reading asked by the neurologist, and started to laugh.

Patients attributed their reaction to the impulse to laugh, without knowing the reason why. Only in one case did the patient say that something weird had occurred to him, making him laugh.

In the rest of the five patients, the stimulation elicited a smile starting from the opposite side of the face, but without mirth.

During the elicited smile patients continued to read.

At the end of the stimulation all patients spontaneously said that they could not keep from smiling, and reported a sensation diffused to the contralateral part of the face, as well as the feeling that the cheek was lifted.

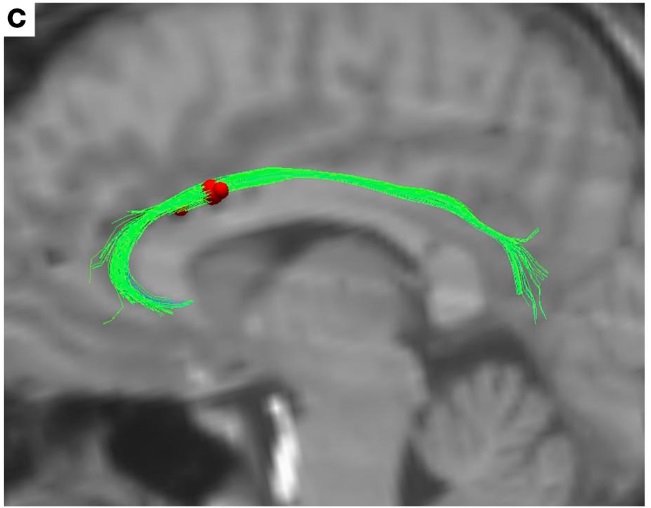

An Emory University study found that electrical stimulation of specific sites of the cingulum bundle can induce laughter accompanied by mirth. (Bijanki et al. 2019)

The cingulum bundle is a bundle of nerve fibers extending from the cingulate cortex, connecting it to other brain regions.

The subjects were three epilepsy patients, and the electrodes that evoked laughter were all located in an approximately 0.4 in (1 cm) span at the supragenual part of the cingulum bundle.

The stronger the stimulation, the stronger the expressions of laughter for everyone.

In the first patient, a 23-year-old woman, electrical stimulation of the left cingulate bundle immediately elicited mirthful behavior, including smiling and laughing, and reports of positive emotional experience.

She reported an involuntary urge to laugh that began at the onset of stimulation and evolved into a pleasant, relaxed feeling over the course of a few seconds of stimulation.

Following the offset of stimulation, the sensation dissipated over the course of a few seconds.

The smile began with a contraction of the muscles in the right cheek, then spread across the face into a natural-appearing smile.

The stronger the stimulation intensity, the more intense the laughter experience.

At 1.0 mA, the patient chuckled involuntarily: "Feeling something."

At 1.5 mA, the patient felt restless and changed in mood: "Just a feeling of happiness."

At 2.0 mA, laughter was added: "It felt the same, just more intense, in a good way… That's awesome!"

At 3.5 mA, the feeling became more intense: "Wow, everyone should have this… I'm so happy I want to cry."

The second patient, a 40-year-old man, received electrical stimulation of the right cingulum bundle.

Smiling was elicited at 2.5 mA, mood elevation was reported at 3.0 mA, and overt laughter occurred at 3.5 mA.

Stimulation of the more posterior electrode contact, in addition to smiling at 2.0 mA, also elicited an urge to move at 2.5 mA.

The third patient, a 28-year-old woman, was asked to rate her feelings of happiness, relaxation, and post-operative head pain on a 10-point scale.

3 V stimulation yielded smiling and laughter, a 10% increase in happiness, a 20% increase in relaxation, and a 20% reduction in pain.

5 V stimulation elicited similar behavior, and a 20% increase in happiness, a 60% increase in relaxation, and a 40% reduction in pain.

At 4 V stimulation, the patient was asked to describe a sad memory, during which she was observed to be smiling, and she described not feeling sad despite accurate recollection.

“I remember my dog dying, and I remember that it was a sad memory, but I don’t feel sad about it right now.”

A case was reported at the Lausanne University Hospital, Switzerland, in which electrical stimulation of the anterior cingulate cortex induced laughter without mirth. (Sperli et al. 2006)

The subject was a 21-year-old man with epilepsy, and electrical stimulation of the right anterior cingulate cortex induced laughter.

Stimulation at low intensity induced only a smile, predominating in the left side of the face, whereas stimulation at higher intensity induced laughter along with smiling on both sides.

The duration and intensity of laughter increased with increasing intensity of stimulation. These electrical stimulations were repeated the following day, and the same phenomena occurred.

The laughter was never accompanied by a sensation of merriment or mirth.

The patient had expressed a depressed mood during most of his stay in the hospital.

His mood did not change during the electrical stimulation of the cingulate cortex. The patient specifically related that he still felt sad, and that his smiles and laughs were involuntary.

In contrast to his emotional state, the smile and laughter appeared to be quite natural, inducing infectious laughter among the attending staff as well.

Superior Frontal Gyrus

A UCLA study found that electrical stimulation of the supplementary motor area can induce laughter. (Fried et al. 1998)

The subject was a 16-year-old female patient with epilepsy, and laughter was induced by electrical stimulation of a small area of 0.8 in (2 cm) square in the supplementary motor area.

The laughter was accompanied by a sensation of merriment or mirth.

Although it was evoked by electrical stimulation on several trials, a different explanation for it was offered by the patient each time, attributing the laughter to whatever external stimulus was present.

- The particular object seen during naming (“The horse is funny”)

- The particular content of a paragraph during reading

- The persons present in the room while the patient performed a finger apposition task (“You guys are just so funny… standing around”)

The duration and intensity of laughter increased with increasing intensity of stimulation.

At low intensity only a smile was present, while at higher intensities a robust contagious laughter was induced.

A German epilepsy center reported cases in which laughter was induced not only by electrical stimulation of the supplementary motor area but also by that of the adjacent premotor area. (Schmitt et al. 2006)

One patient was an 18-month-old boy and the other was a 35-year-old woman.

Laughter was obtained from stimulation of the premotor area near the midline in the child patient, and from that of the anterior part of the supplementary motor area in the female patient.

The female patient reported absence of emotional content: "That is not me!"

The Lyon Neuroscience Research Center, France, reported a case in which laughter was induced by electrical stimulation of the pre-supplementary motor area. (Krolak‐Salmon et al. 2005)

The subject was a 19-year-old female patient with epilepsy, and stimulation of the left pre-supplementary motor area provoked a smile and laughter.

The minimum intensity required to observe this phenomenon was 0.6 mA.

She reported afterward that she felt her lip corners elevating in a forced smile, followed by a real feeling of mirth or happiness.

“At the beginning, I did not feel like smiling or laughing. A moment later, I really felt like laughing, I had a sensation of merriment, like seeing a Laurel and Hardy film.”

She reported later that she could not keep from laughing despite the discomfort of the stimulation.

In contrast, at 0.8 mA intensity stimulation, a smile was observed, then laughter, a moaning, and a dystonia.

Two minutes after the stimulation, she burst into tears, felt sad, and kept a very affected voice for 15 minutes.

“It is not normal, it is not my fault, I can not refrain from smiling and crying.”

The stimulation of the neighboring sites provoked only speech arrests and abnormal face and limb movements.

Frontal Operculum and Insular Cortex

UH Cleveland Medical Center reported a case in which electrical stimulation of the frontal operculum induced laughter. (Vaca et al. 2011)

The subject was a 55-year-old female patient with epilepsy, and electrical stimulation of the opercular part of the left inferior frontal gyrus consistently induced mirth and laughter.

On several occasions, she started laughing during stimulation and stopped at the end of the stimulus.

After termination of stimulation, she made comments such as “You guys are making me laugh,” “Something was making me laugh,” or “That was really funny.”

When asked, she was unable to identify what was funny, but she would describe it “as if somebody was joking with me about something.”

The laughter appeared to be her typical laugh and was infectious, sometimes leading to a general burst of laughter by the physicians and technicians present in the room.

This response was almost perfectly reproduced in a stimulation session on another day.

At the University of Parma in Italy, cases were also reported in which electrical stimulation of the frontal operculum induced laughter. (Caruana et al. 2016)

The subjects were four epilepsy patients, and electrical stimulation of the frontal operculum induced smiling and/or laughter in all patients.

In the first case, a 23-year-old woman, electrical stimulation of the left frontal operculum produced a smile not accompanied by laughter.

The smile was not accompanied by mirth, and the patient did not become aware that she produced a facial expression.

When asked whether she smiled, she responded negatively, stating that the stimulation was completely ineffective.

In the second case, a 30-year-old woman, electrical stimulation of the right frontal operculum interrupted her speech, and produced a smile not accompanied by laughter.

Similar to the first case, the facial expression was not accompanied by vocalization or any postural movement, resulting in a smile and not a laugh.

When asked why she arrested her speech and started smiling, she answered that she was not able to speak anymore, and she was not able to explain the reason why she smiled.

In the third case, a 39-year-old woman, electrical stimulation of the left frontal operculum interrupted her speech, and produced a smile and a laugh.

Subsequently, the patient spontaneously reported that she arrested her speech because she was laughing.

In the fourth case, a 4-year-old boy, electrical stimulation of the right frontal operculum produced a smile and a laugh.

The smiling expression was preserved after the stimulation offset, but without any clear vocalizations.

A case was reported at Capital Medical University, China, in which laughter was induced by electrical stimulation of the insular cortex, a cortex area overlaid by the operculum. (Yan et al. 2019)

The subject was a 21-year-old male patient with epilepsy, and electrical stimulation of the left posterior insular cortex reproducibly induced laughter.

According to his description, he felt happy and had an impulse to laugh inexplicably, which was followed by uncontrollable laughter.

His smile began on the right side of his face and then spread to the entire face.

Basal Temporal Cortex

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University reported cases in which electrical stimulation of the basal temporal cortex induced bursts of laughter. (Arroyo et al. 1993)

The subjects were two female patients with epilepsy, aged 23 and 24, and electrical stimulation of the fusiform gyrus and parahippocampal gyrus at the basal temporal lobe induced cheerful bursts of laughter accompanied by a feeling of mirth.

The laughter of the first patient was experienced as contagious laughter by those who tested her.

She described the feelings associated with laughing in two ways: "The meanings of the things changed" in a funny way and "Things sounded really funny."

The laughter the second patient presented, although similar to her usual laughter, was described by those testing her as more brisk and strident than her spontaneous laughter.

She described a funny feeling, a sense of weakness in the head, sparkles all over and a feeling of happiness and dizziness.

Researchers at Kyoto University also reported cases in which laughter was induced by electrical stimulation of the basal temporal cortex. (Satow 2003, Yamao et al. 2015)

The subjects were two female epileptic patients, aged 17 and 24, and in both cases laughter was induced from the inferior temporal gyrus at the basal temporal cortex.

In the first patient, electrical stimulation consistently caused lifting of the right side of the mouth, followed by facial movements of both sides with mirth.

After the stimulation was over, the patient said, “I do not know why, but something amused me and I laughed.”

In the second patient, electrical stimulation at low intensity and short duration consistently produced mirth without laughter, and it was always accompanied by a melody that she had heard in a television program in her childhood.

The duration and intensity of the mirth increased in proportion to the duration and intensity of stimulation, and she eventually developed laughter with stimulation at high intensity and long duration.

The patient said that the tune appeared funny to her and made her feel amused, but only during the electrical stimulation.

Nucleus Accumbens

A research group at the University of Florida reported a case in which electrical stimulation of the nucleus accumbens induced smiling and feelings of euphoria. (Okun et al. 2004)

The patient was a 34-year-old woman with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and electrical stimulation of the right nucleus accumbens was administered as an experimental treatment.

During the intra-operative evaluation, with the stimulation at 2 V they observed an asymmetry in the smile lines. The patient described her mood as “giddy” during this observation.

With increasing intensities of stimulation of 4, 6, and 8 V, the patient was observed to smile on the left side of her face, and had an experience of euphoria.

The euphoria was described as giddiness, feeling happy and feelings of wanting to laugh as well as feeling embarrassed and self-conscious that she was smiling.

Stimulation on the left side elicited a similar response, and stimulation on both sides resulted in a symmetrical smile with euphoria.

This effect disappeared when the stimulation was discontinued.

Long-term application of electrical stimulation significantly improved the patient's mood and medical condition.

The research group studied laughter induced by electrical stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in six patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. (Haq et al. 2011)

Upon stimulation of the nucleus accumbens, the patients reported a sense of euphoria rapidly followed by a smile opposite to the side of stimulation.

The onset of the smile occurred within 1-2 seconds of stimulation onset in all but one patient, who reported that he had consciously been “trying to keep a straight face.”

In some cases, the smile spread to both sides of the face and even to natural-sounding laughter.

Stimulating the same site with the same intensity reproduced the same laughter.

At stimulation sites where smiles were observed, the mood elevated as stimulation became stronger, whereas at stimulation sites where smiles were not observed, the mood depressed as stimulation became stronger.

A research group at Mayo Clinic also studied laughter induced by electrical stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in four patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. (Gibson et al. 2016)

Smiling was observed in three of four patients with electrical stimulation of the nucleus accumbens. In two patients, smiling was accompanied by spontaneous laughter.

Only one patient did not exhibit obvious signs of smiling or laughter, but reported decreased anxiety and increased mood and energy.

Other patients used words to describe their state of mind as "clear-minded," "less anxious," and "happy."

One patient stated that during stimulation, "When I’m happy, it (obsessive-compulsive disorder) doesn’t bother me as much.”

Another patient experienced a “metallic” smell that accompanied the feeling of well-being.

Upon cessation of stimulation, he asked whether the experimenters could “bring that smell back,” since he associated it with pleasant feelings.

Hypothalamic Hamartomas

An Alabama epilepsy center was treating patients with hypothalamic hamartomas and laughing seizures. (Kuzniecky et al. 1997)

One of the patients was a 30-year-old man, and he was impulsive, angry, and showed aggressive behavior.

He had laughing seizures since the newborn, and they occurred 1-3 times a day.

In his seizures, he would laugh, turn his head to the right, followed by a partial complex seizure.

He also reported multiple small seizures per day characterized by a funny feeling in his head followed by a brief irresistible laugh.

Electrical stimulation of the hypothalamic hamartoma reproduced the small seizures.

The patient reported a funny feeling in his head followed by laughing lasting 15 seconds. Three subsequent stimulations reliably reproduced the laughter seizure.

Coagulation of the hypothalamic hamartoma cured the laughing seizures, and reduced irritability and aggressive tendencies.